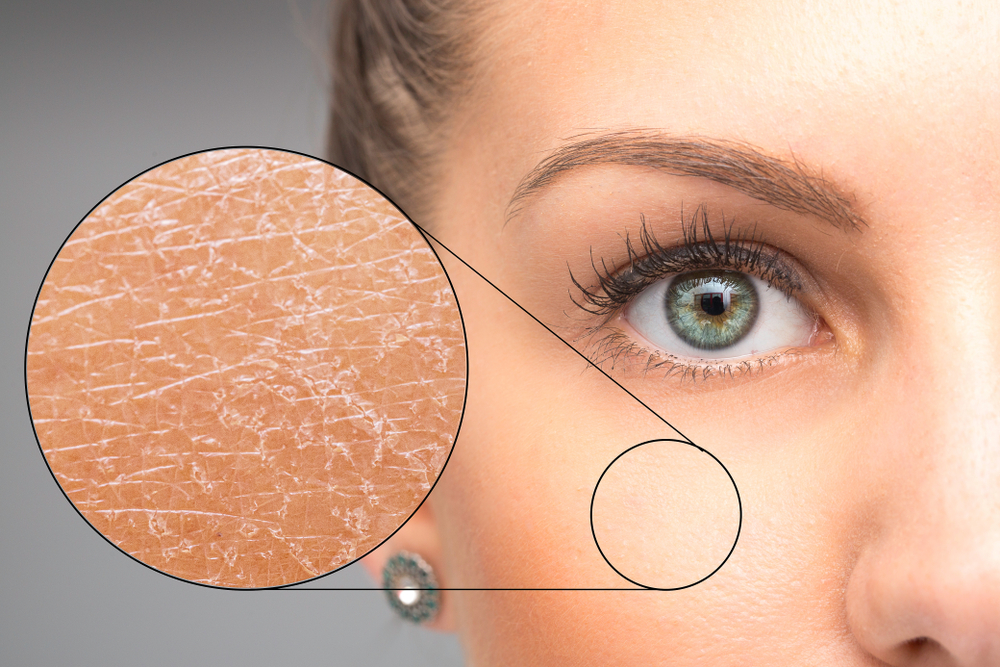

Eczema (also known as dermatitis) is a non-contagious, inflammatory dry skin condition that can affect people from early infancy to old age and it is incredibly common.

The National Eczema Society estimates that the most common form, atopic eczema, affects one in five children and one in 10 adults in the UK[1]. Eczema is particularly common in infants, and 15 percent of children have it[2]. About 60 percent of those with eczema will experience symptoms by age one, and another 30 percent will experience symptoms by age five[3]. Although eczema most commonly shows up before the age of five, adolescents and adults can also develop the condition. However, it is unusual for someone to develop it for the first time after 60, so this should be investigated as it may be linked to a more serious underlying condition.

Eczema is a complex condition. It is typically an episodic disease of flares (exacerbations, which may occur as frequently as two or three times each month) and remissions; in severe cases, disease activity may be continuous[4]. Genetic predisposition, skin barrier dysfunction, environmental factors and immune system dysfunction are thought to play a role in its development.

It can be worsened or ‘triggered’ by exposure to many different things, including allergens such as pet dander, dust mites or pollen. Other common triggers include specific foods, cosmetics, soaps and detergents. Exposure to perfumes and cleaning products can also irritate eczema. For some people, weather changes (especially heat or dry winter air), illnesses such as the common cold, or even stress may make eczema worse.

Dr Nisa Aslam, a GP with a special interest in dermatology and an adviser to the Skin Life Sciences Foundation (www.slsf.uk), focusses on the link between allergies and the skin condition – eczema.

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of eczema may include a red rash or red patches of skin, especially inside the folds of the elbows and knees, intense itching and dry skin. During a flare up it can also be red, cracked, raw or bleeding. Symptoms can even include blisters and the skin may change colour. The location of eczema may change with age. In infants and young children, eczema is usually located on the cheeks, outside of the elbows and on the knees. In older children and adults, eczema is typically on the hands and feet, the arms and on the back of knees.

With eczema, the skin is often unbearably itchy – the urge to scratch can feel irresistible. Infants with eczema often rub the affected part against bedding or other things to try and relieve the itch. Giving in to the urge and scratching the skin can then lead to a bacterial infection with Staphylococcus aureus, herpes simplex virus infection or superficial fungal infection. Alongside the painful physical symptoms of eczema, there can also be psychosocial issues, such as missing school or work, disturbed sleep, anxiety, depression, reduced self-confidence and other mental health problems[5].

Influencing factors

It is conclusive that allergy plays a role in some patients’ eczema[6] and for some there are also hereditary factors. If both parents have eczema there is a 50% chance that the offspring will develop it. Likewise, children born into families that have a history of allergic diseases such as asthma or hayfever are at an increased risk for developing eczema.[7]

Eczema is considered to be part of the ‘atopic march’. The atopic march involves the diagnosis of eczema during infancy, followed by food allergy, allergic rhinitis and asthma, typically in that order. Studies show up to 80 percent of children with eczema develop asthma and/or allergic rhinitis later in childhood.

Scientists have found that people who have a protein deficiency known as Filaggrin deficiency are at increased risk for developing eczema. Emerging research suggests that some people with eczema have a genetic flaw that causes a lack of proteins called filaggrin and loricrin in their skin[8]. These proteins help form the protective outer layer of our skin and keep out germs. A lack of filaggrin dries out and weakens the skin barrier causing increased water loss from the skin. This dryness can be a trigger for eczema and makes the skin vulnerable to irritants, like soaps and detergents. It also makes it easier for allergens to enter the body.

Whilst scientific knowledge in the area is constantly evolving, one thing is clear. Individual trigger factors can vary from person to person and more people may be affected by more than one trigger factor that can cause a flare of their eczema. Many different factors have been proposed as triggers for eczema and the identification of individual triggers for each patient is crucial for the successful management of the condition and avoidance may allow for longer periods of remission. Helping patients identify their triggers can be helpful in managing the condition. Some triggers may be easier to identify than others. Here’s a summary of triggers I talk to patients around:

- Contact irritants – ask your patient about any recent changes in soaps and detergents, especially in people with previously well-controlled eczema. Cigarette smoke can also irritate the skin, in the same way as it irritates lungs and eyes. All skin irritants can trigger eczema by disturbing the skin barrier.

- Irritant fabrics – be aware that some fabrics can act as irritant allergens. For example, synthetic fabrics and wool tend to itch and irritate the skin, whereas silk is often closely woven, thereby impeding the flow of air, and some people are allergic to the sericin protein in silk. Cotton fabric is usually the best recommendation; however, its structure contains short fibres which expand and contract, causing a rubbing movement that can irritate delicate skin. The dyes used in coloured cotton garments can also increase the risk of a sensitivity reaction.

- Skin infections — Staphylococcus aureus is implicated as both a causal factor and a trigger factor for atopic eczema. Other organisms implicated include streptococcus species, Candida albicans, Pityrosporum yeasts, and herpes simplex.

- Contact allergens — look at preservatives in topical medications being used by the patients as well as perfume-based products, metals, and latex.

- Inhalant allergens — ask about symptoms around pets and pollen, especially in older children and adults with seasonal flares, asthma, or rhinitis, and in children over three years of age with atopic eczema on the face, especially around the eyes. Sensitivity to airborne allergens may result in presentations with flares on the head and neck.

- Hormonal triggers — be aware that changes in hormone levels can affect the symptoms of atopic eczema in some women, for example premenstrual flares of eczema can occur, and pregnancy can adversely affect eczema in some women.

- Climate — extremes of temperatures can affect atopic eczema. There is a seasonal variation in the pattern of atopic eczema, and most people are aware of improvements in their eczema during the summer (with worsening symptoms in the winter). However, sweating induced by heat or exercise can provoke a flare of eczema at any time of year. Sweat leaves a salty residue that dries out the skin and it can also induce a histamine reaction and itchy skin.

In real World Research, carried out on behalf of Typharm, with 1,000 participants who have eczema or psoriasis, three quarters of people (77%) were concerned that when the weather heats up, they may have to show more skin which they consider unsightly because of their skin condition. As a result, 68 percent of those polled said they wear more clothing than they would like to when it is warm because they feel they need to cover up. Half (48%) do this to prevent others from seeing their skin while 33 percent do so to prevent flare-ups. Forty percent admit this means they are sometimes sweatier than they would like and 31 percent say they are sometimes too hot. Wearing more clothing in warm weather will exacerbate the effects of heat and sweating on skin conditions.

- Dietary factors — ask about itch or redness after certain foods (immediately or hours later), diarrhoea, vomiting, and/or poor weight gain. Milk, egg, wheat, soy, and peanut account for about 75% of the cases of food-induced eczema. Most people, except the most severely affected, will not benefit from food allergy testing and there can be a high rate of false positive results. This can lead to misdiagnosis and unnecessary food avoidance.

To help parents navigate the complex and emotionally challenging early days of a child’s diagnosis with eczema, Allergy UK’s Dietitian Service offers specialist allergy advice to help inform and guide parents of children from 0-5 years old who are presenting with symptoms of food allergy.

Treatment

Whenever someone presents with the symptoms of eczema, the severity and the psychological impact should also be assessed. A stepped approach for eczema is usually recommended:[9]

- Provide information about the condition and reassure that it is not infectious.

- Emollients are the first-line treatments during both acute flares and remissions of the condition.

- For exacerbations/flare-ups, the use of topical steroids should be considered for red, inflamed skin. The lowest potency and amount of topical corticosteroid necessary to control symptoms should be prescribed, depending on the severity of the flare. Corticosteroids can be given in a variety of formats to suit clinical needs and patient preferences.

Creams, ointments, lotion, gel, and/or scalp applications are all available in a range of potencies and as proprietary and non-proprietary products. A newer addition to the options available is Fludroxycortide tape, a transparent, waterproof, medicated, surgical tape which can be cut to the shape and size of the affected area, making it flexible and versatile for the patient. Unlike creams and ointments, fludroxycortide tape does not moisturise the wound bed. It works effectively on the affected area by delivering a uniform metered dose of steroid over a 12-hour period. The tape also provides a barrier and hence helps the patient avoid any challenges that allergens may present.

- If recurrences are persistent or severe, consider calcineurin Inhibitors. If there is persistent, severe itch, or urticaria, a one-month trial of a non-sedating antihistamine should be considered.

- If itching is severe and affecting sleep, a short course of a sedating antihistamine should be considered (if appropriate).

- If there is severe, extensive eczema, a short course of oral corticosteroids should be considered.

- If eczema is weeping, crusted, or there are pustules, with fever or malaise, secondary bacterial infection should be considered, and antibiotic treatment should be prescribed

Providing appropriate information on the nature of eczema and advice on the importance of adherence to skin care measures and avoidance of trigger factors (where possible) is essential for maintenance of the condition and management of flares.